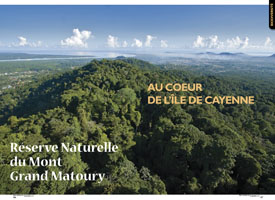

The slopes of higher ground between the coastal plains of the Amazon and the Orinoco are home to one of the last areas of primal forest along the coastal strip. Mont Grand Matoury (234 metres) in French Guiana rises up above the plain and attracts the gaze of those living in the town of Cayenne and even the suburb of Matoury. It proudly displays its Amazonian forest, which is still intact thanks to its having been protected as a national nature reserve since September 2006.

We set off to discover it at dawn when the slumbering forest is still draped in mist.

After barely 15 minutes’ driving, we arrive at the beginning of our trek. In the cool of early morning the landscape is bathed in light and silence. Our walk begins in the morning cool in a wood with canna, Schefflera, Cecropia (‘trumpet trees’) and comou and maripa palms. The vegetation indicates that the forest has been slowly regenerating itself since the La Mirande rum factory closed down over sixty years ago (and of which only a few remains still stand) where they used to cut down the surrounding trees for firewood. At the foot of a maripa palm a somewhat surprised agouti disappears when it sees us arrive. We had just caught it hard at work carrying out its job as forest gardener, propagating and burying the seeds of a large number of tree species all over its territory. Nature is gradually awaking. The rising sun acts as the conductor for a concert of bird song as they whistle, call, chirp, chirrup, or warble depending upon their own musical score, taking over from the night-time melodies of frogs or insects, depending upon season.

We cross a little stream with Cyathea on either side, tree ferns bearing aloft their coppery-coloured crosiers. The limpid water sings as the ballet of little fish swim upstream. The sight of shrimp playing at hide-and-seek among the rocks indicates just how clear the water is. A bit further on there is a blue-backed manakin waiting to greet us amidst the curtain of creepers, decked out in his red cap and incredible blue cape on his back. These little passerine birds are part of a family specific to tropical America, and the males gather to parade. In the dancing light filtering through to the undergrowth they compete with each other before our eyes to attract the females.

It is already twenty minutes that we have been fascinated by the atmosphere and intoxicated by the fragrance of the incense trees. A signpost indicates the beginning of our circuit, and we are now going to enter the great primal forest. There are two officially listed circuits making up Les Sentiers de La Mirande, one 2.5 and the other 2.8 kilometres long. They are there to help the public safely discover and learn about the Amazon forest area, and all you need in the way of equipment for the 3 1/2 hour’s walk is a good pair of walking boots. We are moved at the idea of exploring this forest in the footsteps of the first naturalists and explorers such as the eighteenth-century botanist Jean-Baptiste Aublet. Since it was near Cayenne it was one of the first forests to be explored. Many of the new species that were discovered were described as being from this area. The Mont Grand Matoury Nature Reserve is a living history museum of the natural sciences in the region.

We start going up a gentle slope. We walk to the accompaniment of a red-necked woodpecker, two dull notes like someone hammering a nail in, which has earned it its local name of the ‘charpentier’ (carpenter). But very soon we hear the characteristic call of a screaming piha piercing the hush of the forest to welcome us. The environment now looks very different from the wood we went through at first. Tall trees rise up like living monuments from the undergrowth of Astrocaryum palms. Holy kapoks, hymenolobia with their tentacle-like buttress roots, monkey pot trees with their wizened bark like a parchment of years gone by, and then the strangler figs are all testimony to how mighty plants can be. These giants found along the path merit closer attention, and have information panels at their feet.

The slope starts to get a bit steeper but our efforts are rewarded by the subtle, sweet, powerful fragrance of an orchid enveloping the undergrowth (unless it is of one of the flowers of a canopy creeper, that is). We easily catch a glimpse of an Anolis despite its agility, a graceful lizard displaying the blue pockets beneath his throat to dominate his territory in style. We look at the mass of foliage. A trogon is meditating on its branch, a wedge-billed woodcreeper is climbing the silvery-grey trunk of a goupie. We are presented with a whole jungle suspended in the air with the proliferation of creepers and epiphyte* plants. The bromeliads hanging in mid-air trap reservoirs of water between their leaves, and act as little ecosystems – nurseries for a multitude of insects and even amphibians.

All the way along this discovery trail through the primal forest we notice the dainty and intricate foliage of a large number of ferns, some of which are very rare though in fact present in large numbers on this protected site. We take advantage of the openings in the forest due to fallen trees and branches to admire the shapes of the densely packed tree crowns outlined against the sky as if in illustration of the outstanding biodiversity of this forest.

Our eyes are bombarded by the light of green photons from this incredible canopy. An entire ecosystem in its own right stretches out on the roof of the forest. It is where the highest levels of sunshine are and there is an abundance of diversified food resources, meaning it is one of the layers of the forest to have the largest number of species. Flowers can flourish there, accompanied by a whole range of nectarivore birds and hummingbirds that play a very important role in pollination, as insects do. The flowers seem to be a holy grail for the hummingbirds which flutter around in one giant ballet to get at the nectar. Specific associations are even more typical here than they are elsewhere, leading to interdependences between plants and animals and some remarkable adaptations. The reproduction and hence existence of a plant species can depend entirely on one species of pollinating insect, for instance, and only the beak of certain hummingbirds might be the right shape to reach the bottom of the calyx.

We go back into the undergrowth. The freshly turned earth and persistent smell tells us that a herd of peccaries have been through here. Further on, a slaty-backed forest-falcon is concealed in the foliage of the large crown of an acacia tree. This bird of prey seems to be patiently waiting to catch the last cicadas of the season that chirrup lazily when the sun breaks through the clouds.In the damp shady corner of a deep thalweg we admire the flickering metallic blue of fluttering morpho butterflies, a sight we could watch forever against the emerald green backdrop. It is nice to pause for a moment in this valley cut into the Precambrian rock, clearly showing how the Guiana Shield is advancing along the coast. The stream at our feet is home to a population of orangey and pink Cayenne stubfoot toads which are endemic* to French Guiana and only found in a few rare places. Mont Grand Matoury is where the species was discovered and first described. Not far from where we have halted a large group of squirrel monkeys are busy feasting on fruit and seem not to be afraid of us as they noisily jump around up in the treetops.

In certain places and depending upon the season the paths are covered in a carpet of flowers, with pink petals from hibiscus plants once the rainy season ends, bright yellows from the green ebony trees in the middle of the dry season, and the violet colour of jacarandas at the end of the year.

Elsewhere ethereal spikemosses covers the ground, looking like prehistoric flora.

In the plant litter we spot saprophytic gentians with their opaline flowers against the patchwork of leaves. These plants do not have any chlorophyll but make up for this by feeding on organic matter decomposing in the soil. A host of invertebrates is also crawling around beneath this carpet of leaves. They are hard at work decomposing and rapidly transforming the organic matter. It is life after death that can be seen at work here, leaving little chance for the soil to obtain much depth. And so the trees that we see have developed many tricks to maintain their stability despite the fact that their roots do not go down far beneath the surface. They have large, majestic buttress roots like the hymenolobia, or stilt roots like the trumpet trees, or else creeping roots like the souari trees.

We reach the summit, guided by this dense network of roots which act like so many steps on a natural staircase. A particular form of forest is to be found at the top of the plateau of laterite crust. There is virtually no soil and so the forest is made up of stunted, twisted trees with a jumble of creeping roots on the bare rock echoing the knotted curtains of creepers found in great numbers here.

We encounter another group of walkers and stop for a moment to admire some dendrobates together, spectacular neotropical frogs whose colours warn any predators that they are highly toxic. The Mont Grand Matoury Nature Reserve has a population with a unique colour patterning.

We have now been walking for two hours in the primal forest, taking our time to discover all its many riches. Suddenly, as we start down the slope, we get a panoramic view out over the isle of Cayenne. A small opening has been cleared in the forest to offer a unique view point from the slope out over the open horizon, stretching far into the ocean. Here we can clearly see just how important it is to protect this natural area at the heart of a rapidly expanding urban fabric.

It is early December and the rainy season will soon be upon us. The clouds driven inland by the tradewinds hug the land when it rises to 150 or 200 metres. The forest acts as a barrier to their progress and certain slopes are bathed in mist for much of the day, creating a genuine microclimate in certain spots which encourages the biodiversity we have witnessed. Not only are certain species endemic to the spot, the biodiversity here is all the more fascinating as we are at the biogeographical intersection of the influences of Amazonia and the Guiana Shield region. And so within the range of species to be found in the great primal forests of the interior are some which are at the limits of their geographical area, and more associated with Amazonia (plants and insects in particular).

We carry on down the southern slope of the hill and the sound of the Mancellière waterfalls soon covers the typical noises of the forest. With its white foam against black rock, the river is drumming on the mossy rocks with their unusual little flowers, as if announcing the forthcoming French Guiana carnival. After our walk we delight in the pure cool water, a treasure trove at the heart of this urban ‘island’.

On the way back we stroke the feathery silver-coloured foliage of a melastomataceae whose berries are dark blue once ripe but like blood-red pearls beforehand, contrasting with the shades of green and never failing to arouse the appetite of the brightly coloured and greedy tanagers and manakins. A long-horned beetle is exploring a log. It is a like a multi-coloured harlequin displaying his colours – the carnival cannot be far off now!

English

English Français

Français  Português

Português

Télécharger l'article en PDF est réservé aux abonnés Web !

Télécharger l'article en PDF est réservé aux abonnés Web !

Pas de réaction

Pas de réaction Comment!

Comment!

Voyages avec Tooy. Histoire, mémoire, imaginaire des Amériques noires : Editions Vents d’ailleurs, 2010

Voyages avec Tooy. Histoire, mémoire, imaginaire des Amériques noires : Editions Vents d’ailleurs, 2010

Guyane. Produits du terroir et recettes traditionnelles. L’inventaire du patrimoine culinaire de la France : Editions Albin Michel, 1999

Guyane. Produits du terroir et recettes traditionnelles. L’inventaire du patrimoine culinaire de la France : Editions Albin Michel, 1999

Alunawalé, un voyage à travers les milieux naturels de Guyane : Office National des Forêts, 2009

Alunawalé, un voyage à travers les milieux naturels de Guyane : Office National des Forêts, 2009

Augusta Curiel, Fotografe in Suiriname 1904 – 1937 : Libri Misei Surinamensis, 2007

Augusta Curiel, Fotografe in Suiriname 1904 – 1937 : Libri Misei Surinamensis, 2007