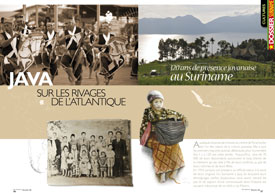

Only a few minutes from the centre of Paramaribo is one of the beating hearts of Javanese culture. It has been there since the first Javanese migrants came across 120 years ago this year. Today there are over 70,000 Javanese who, to the sound of great festivities, are remembering their ancestors and the island they hailed from.

In 1954 some of them undertook the arduous journey back to the land of their fathers. We have retraced their footsteps to recount their sometimes painful stories and to tell of the hopes of this community whose history is often but poorly known in French Guiana.

Mrs Kim Sontosoemarto, the head of the Sana Budaya cultural centre, screws up her eyes. Her face becomes serious as she concentrates on my question. How come Javanese culture has managed to survive over 20,000 kilometres away from the island where it originated? Nearby in Paramaribo the Indonesian festival is in full swing in the August heat of 2009. The cultural centre is in the middle of a market of little wooden shacks owned by the Javanese, where market gardeners, fishermen, and even a music seller, a fan of soul music, display their wares every Sunday. I am only a few kilometres from the town centre but I am at the heart of one of the only communities of its kind outside Java.

Symbolically, the place is dominated by a giant gunungan statue, 9 metres tall, representing the primordial forces of life in Javanese shadow puppet theatre (wayang). The climax of the festivities take place at its foot when the elders come to perform on a gamelan, a set of traditional musical instruments that accompanied the dance and trances of the Jaran Kepang (cf. inset). But nothing seemed to indicate that this centuries-old culture would take root so far from home.

Mrs Kim has opened her eyes again. No, she says, it wasn’t easy getting this far. In order to explain to me why her people are now on the shores of the Atlantic, she has to go back to the circumstances which pushed the Javanese to leave their homeland 120 years ago.

The arrival of the Javanese in Surinam

In 1863 the abolition of slavery by the Netherlands caught the settlers in Surinam totally unawares. Their plantations were based on an unpaid workforce subjected to the harshest of treatment. Following the example of the English and French in the region, they quickly decided to recruit agricultural workers from the British-ruled Indies.

This system soon showed its limits. The Batavians complained that they were unable to get the most robust individuals as they were “served” after the English and the French. At least this is how they explained the terrible loss of life that occurred between boarding in India and arriving in Surinam. It is more likely that the lack of care and hygiene on board the ships and in the barracks in Surinam got the better of even the most robust individuals, as a Dutch doctor sent to inspect the new arrivals on disembarkation declared. What is more those who had “signed up” had to serve for 5 years in Surinam on pain of punishment for what was that viewed as the equivalent of desertion. Their labour was meant to cover the cost of their recruitment, transport and upkeep. They were paid a meagre stipend, though it was often withheld or recuperated as a fine for the slightest deviation. Unsurprisingly, complaints of poor treatment regularly came to the attention of the British Consul in Paramaribo for punishments similar to that formerly meted out to the slaves.

This became such a regular occurrence that Britain tacitly decided to intermittently suspend the shipping of coolies to Paramaribo.

These migrants also came with two major disadvantages for the Dutch. Firstly, as British nationals, the Indians were free to ask the British Consul to overturn punishments handed down in the plantations. Secondly, their increasing numbers meant they rapidly threatened to become the majority population in this Dutch colony.

Thus after intense negotiations with the Governor of the Dutch Indies, 62 Javanese men and 32 Javanese women arrived in Surinam between August and November 1890. Not all of them seemed to be fully informed about what was awaiting them. Thus when their rights were read out on arrival – particularly the fact that refusal was punishable by imprisonment – some of them headed straight for the prison. Nevertheless, all started work over the course of the following year. This first wave of immigration was presented as an experiment and was followed by many others over the years. The Javanese were said to be docile, hard-working, and less irresolute then the Indians.

The conditions in which people were recruited from Java were doubtful at best. “Rounders up” were paid according the number of people they recruited and often took advantage of the destitute, victims of the lack of land in Java, of taxes levied by the colonial administration, and of a lack of education. Unscrupulous recruiters dangled promises of land, marriage and easy money. When that did not suffice, fictitious gambling debts could be fabricated as an additional means of coercion. Infringements of the stringent Javanese social rules relating to forbidden love or adventurism were further motivations for migrants to go to the “land over there” (tanah seberang) across the oceans.

In the 1930s circumstances improved for the migrants, as the Dutch authorities felt that the absence of an established population was hindering the development of the colony. Penal sanctions relating to infringements by plantation workers were abolished in 1931. In 1932 the authorities abolished the contracts of service hitherto used, limiting contracts to a maximum of one year, and paid in full the migrants’ transport costs. These measures were supplemented by the migrants being offered land at the end of their contract if they decided not to return home.

There were now projects to build autonomous villages by “Javanising” Surinam with the transfer of 100,000 Javanese over a period of ten years. The idea was that they would develop rice farming both for the needs of the colony and for export. But the war put paid to this experiment which began in 1939.

From 1896 to 1939 nearly 30,000 Javanese migrants arrived in Surinam, Mrs Kim explains to me, of whom only a fifth decided to return home. But things were not easy for those who did stay, sometimes despite themselves, as Mrs Kim explains as she continues her tale.

Solidarity – The basis of integration and the preservation of their cultural heritage

The ordeals they underwent created powerful bonds of solidarity between the members of the Javanese community. Thus for instance there was a fraternity amongst those who travelled on the same boat. Age determined social status and the respect accorded to an individual, as the experience attributed to the elders was synonymous with wisdom and knowledge which were meant to guarantee group harmony (rukun), an essential virtue in Javanese society. People who had attended an Islamic religious school (pesantrèn), and interpreters who acted as intermediaries between plantation owners and workers, enjoyed a respected social status. However, these positions of responsibility were determined by the authorities and not by the community.

But the community did manage to preserve the key rites of its original culture: slamatan (propitiatory* shared meals), sajèn (offerings to the ministering spirits), nyekar (pilgrimages to the tombs of the departed) have all retained their function today. In 1918 the first Javanese cultural foundation, Tjintoko Moeljo (poor but respectful), was set up on the Marienburg plantation with the goal of providing economic and social support, as well as having cultural and spiritual aspirations like many organisations subsequently created on the same model.

Cohabitation with other ethnic groups did not necessarily come easily. Creoles and Hindus viewed the more docile Javanese as the new slaves. The feeling of privation and threat thus persisted until after the Second World War.

Malaysian independence, which though declared in 1945 only took effect in 1949 after a war of emancipation, marked a new phase for the community in Surinam. It intensified nationalist feelings, which were also encouraged from the 1950s onwards by representatives of the Indonesian government. Thus in 1946 the first Javanese political party was created (Kaum Tani Persatuan Indonesia-KTPI). Its main objective at the time was to establish the right to return to Indonesia.

Nowadays the 70,000 descendants of the Javanese migrants are to be found in all sectors of Surinamese society. They have managed to obtain numerous positions in the public sector (in health and teaching), as well as supplying the national parliament with its president in 2004. Some of them have also done well in the private sector and in the arts. Their culinary heritage has endowed Surinam with the well-known Bami (fried noodles) and Nassi (cooked rice) that are sold in numerous warungs.

Ties have been formed between the two countries, especially between families who have been separated by history. Mrs Kim pauses, and evokes the lot of the Javanese returnees who were part of the Mulih nDjowo movement (“return to Java”) in 1954. She admits that she does not know what became of them. This aroused our curiosity and we decided to find out more.

The story of the returnees

Djakarta, the capital of the Indonesian Republic, late September 2009. It used to be called Batavia, and this was where the migrants’ voyage began 120 years ago. Nowadays the town has 12 million inhabitants in a country of about 240 million. Indonesia is gigantic. It is easy to understand the fascination it exerted over Surinamese of Javanese origin at the time of independence.

With the help of Mr Saimbang at the Surinam Embassy, we tracked down Mr Sarmoedjie, a retired colonel. He was one of those who returned from Surinam. In fairly fluent English, he told me his story and that of his compatriots. In 1954 he had been just eight years old.

The initiative had originated in one of the movements to return to the home country headed by a charismatic leader. Contact had been made with the Indonesian authorities, who had promised 2.5 hectares of land per household. The initial destination was Lampung, separated from Java by the several dozen kilometres of the Sunda Strait. Java was overpopulated and had been unable to provide any land. A second wave of returnees was meant to follow, so some people were confident enough to leave behind part of their family when they boarded the Langkoeas, which set sail in late 1954 carrying 1018 people. It was the only ship to make the voyage.

The arrival in Tongar

The village of Tongar lies to the west of Sumatra and north of the town of Padang [cf map], in the region of the Minangkabau. It is a magnificent place that is sadly notorious for its earthquake risk. We were therefore to land in Pekanbaru, to the east of Sumatra, so as not to find ourselves caught up in the crowds of rescue workers who had arrived as a result of events on 30 September 2009. We would go by road to Bukittinggi, then Lake Maninjau (cf. photo on the right of first page), before heading for Pariaman and finally Simpang Empat. There, we were to call one of Colonel Sarmoedjie’s contacts, who suggested we meet a bit further on along the road. Basar Surdi had been fourteen years old when he left Paramaribo, and has lived at Tongar ever since arriving there in 1954. He and his friend Sarmidi were to tell me the story of the Surinamese village.

On arriving where they were to settle in Tongar on 15 February 1954, the returnees had to clear the patch of virgin forest that had been allocated to them. Nothing had been prepared. They had to build their own houses or walk 5 kilometres to the nearest village. The volcanic terrain was a lot hillier than expected, tigers prowled around the villages and monkeys and warthogs ruined the crops. Some lost heart and went to the Indonesian towns or even returned, dismayed, to Surinam. Work was available in the nearest town, Pekanbaru, where oil had just been found. They often had better skills than the local workforce – some became mechanics, for instance, for the American oil companies.

Nowadays only 34 or so of these migrants remain in Tongar, with an average age of sixty, and they live surrounded by their children and grandchildren. Basar Surdi is one of them.

Basar chose to become a farmer in Tongar and he became involved locally in projects to develop his village. The original rice fields have now given way to palm oil plantations which are far more profitable. Palm oil is used in the cosmetics and food industries (especially margarine in the West) and is the basic ingredient in a new biofuel. This monoculture has been responsible for the destruction of part of the forest of Sumatra. Within ten years 24% has been lost at the hands of profit-hungry national and foreign companies. The palm trees are harvested for a few decades at most, leaving behind impoverished soil that cannot be used for any other crop. Nowadays there is a school and mosque in Tongar, as well as the branch of a palm oil company. In a cruel twist of fate the company is claiming ownership of the land on which Tongar is built, the same land that the Indonesian government had promised to the returnees in 1954. But the deeds were never handed over to the inhabitants who now find themselves at the mercy of the palm oil producers.

Last year Sarmidi, the oldest of the returnees, went back to Surinam for the first time since he had made the crossing on the Langkoas in 1954. His family still lives in Surinam, as do the families of Basar and of Colonel Sarmoedjie. He was surprised by what he found there – a prosperous land of wealthy Javanese who owned fine houses. But it should be noted that once the returnees had left, the colonial government of Dutch Guyana, fearing that the exodus would increase, made it easier to purchase property.

But at the age of seventy-six and proudly sporting a T-shirt of the Surinam football team, he has no regrets. Like his companions in Tongar, he pursued his dream to the end which was also that of the other returnees, that of discovering a country he did not know and which was the land of his ancestors.

JARAN KEPANG, THE HORSE DANCE

One of the most popular Javanese traditions in Surinam is the very spectacular jaran kepang (woven horse) dance, so named after the figurine of woven plant fibre that the dancers hold between their legs. This dance is unique in America and performed at Sana Budaya (the Javanese cultural centre of Paramaribo) in August.

The spectacle is accompanied by a gamelan, a set of traditional musical instruments composed primarily of metallic percussion instruments and especially cymbals, metallophones, and gongs. The strong rhythms provide the dancers with the requisite inspiration such as that of the barongan (the dragon) and Tembem and Pentul (guardian masks).

During the jaran kepang trance, ten or so dancers in traditional dress and make-up go into a hypnotised trance (mabuk). They are watched over by a spiritual leader in charge of containing the supernatural forces (endang) causing the trance.

The performance comprises three parts: the codified choreography of a “kembangan” dance precedes the first trance phase during which the dancers behave like horses. In the next phase (laisan) the dancers behave like other animals (monkeys, tigers, and so on). They adopt the same attitude and go so far as to eat grass, glass, burning coals, or even open a coconut with their teeth.

The jaran kepang dance is performed for important occasions such as circumcision (sunatan), marriage, a woman’s first pregnancy, the Bersih (the annual village festivity), and the Javanese New Year (the first day of the month of Sura). Now it is also performed for birthdays and other rites of passage that mark the life of the community or an individual.

English

English Français

Français  Português

Português

Télécharger l'article en PDF est réservé aux abonnés Web !

Télécharger l'article en PDF est réservé aux abonnés Web !

Pas de réaction

Pas de réaction Comment!

Comment!

Voyages avec Tooy. Histoire, mémoire, imaginaire des Amériques noires : Editions Vents d’ailleurs, 2010

Voyages avec Tooy. Histoire, mémoire, imaginaire des Amériques noires : Editions Vents d’ailleurs, 2010

Guyane. Produits du terroir et recettes traditionnelles. L’inventaire du patrimoine culinaire de la France : Editions Albin Michel, 1999

Guyane. Produits du terroir et recettes traditionnelles. L’inventaire du patrimoine culinaire de la France : Editions Albin Michel, 1999

Alunawalé, un voyage à travers les milieux naturels de Guyane : Office National des Forêts, 2009

Alunawalé, un voyage à travers les milieux naturels de Guyane : Office National des Forêts, 2009

Augusta Curiel, Fotografe in Suiriname 1904 – 1937 : Libri Misei Surinamensis, 2007

Augusta Curiel, Fotografe in Suiriname 1904 – 1937 : Libri Misei Surinamensis, 2007