At the break of dawn, and amidst many multicoloured wooden two-mast tapouilles facing the Mahury, we get on board the launch to Grand Connétable island nature reserve. Today we are going to visit the largest marine nature reserve in France’s overseas territories.

In the days of sailing ships this island stood guard over the port of Cayenne. After three or four weeks at sea it made it possible to correct the route of ships and so prevent them from going aground on the terrible tidal flats or many mudflats on the approach to land. It was in these days that it became known as “Bird Island”. Ship captains used to enjoy letting off a canon to make the thousands of birds living there take to the air, and it became a tradition marking the end of the voyage.

As we leave the estuary with the sandy beaches of Montjoly on one bank and the Marianne polder mangrove forests on the other, a group of costeros let us watch them for a few minutes. These little dolphins found along the coast of French Guiana are fairly shy and do not come near the boat.

With the Rémire Islets to our left we head south-east. In the distance a silhouette starts to emerge which could be that of a boat. As we get nearer we get a clearer glimpse. Its unusual shape leaves little doubt: this is the island of Grand Connétable. All the way there the sun beats down, giving us an idea of what our day is going to be like on the island. This island is the only one in French Guiana not to be wooded, and there is very little in the way of shade. Seeds and clouds merely pass overhead before reaching Mount Kaw, which we can make out behind us in the distance.

After an hour and a half we arrive in the waters of the reserve. In front of us stands the rock that is home to the only colony of seabirds between the two great South American rivers, the Amazon and the Orinoco. After this rock there is nothing else on the horizon, just the ocean and a few tiny shrimping vessels far away out at sea.

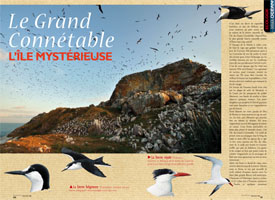

The birds are already wheeling and diving around us as they fish. There are hundreds of them, white ones, brown ones, black ones, small ones, and very large ones. Every year from April to September the island of Grand Connétable is home to several thousand seabirds come from the Caribbean and the Brazilian coast in order to breed. It is for this reason that it was classified as a nature reserve in 1992.

We are downwind of the island and can smell the strong omnipresent odour of the guano* in which the island is covered when the birds are there. You find the same odour in all bird colonies around the world, and it is synonymous with seabird paradise, protected sites where they are left totally undisturbed. To complete the picture you need to remember the deafening noise produced by 3,000 pairs of laughing gulls nesting on the island.

Human activity is one of the major causes limiting the population numbers of seabirds. In the past, people used to take eggs, chicks, and adult birds to eat them or simply for the fun of the hunt, and this had a major local impact, but nowadays at Grand Connétable island such practices are a thing of the past.

A little cove protected from the swell and dominant winds enables us to land in a somewhat hazardous operation. We have to jump out of the boat onto the only little rock jutting out above the surface of the water which, I am told, is not slippery. The last person has to swim ashore after mooring the boat about fifty metres from the island. This way of landing is admittedly not practical, but it is one of the best guarantees to ensure that the site is left in peace, and therefore nothing is done to make it any easier.

We finally set foot on the island, and now all you have to do is reach the plateau twenty-five metres up by following a narrow pathway hugging the hillside, where a single misstep would be unforgiving. Once we are up the steep little slope we discover an amazing sight. Everywhere there are dozens of majestic magnificent frigatebirds. Between 3,000 and 4,000 come to the island, about five percent of the population in the Caribbean. With their 2.5 metre wingspan they are awe-inspiring and make full use of this fact when feeding, as they are known to steal the food of other species on the wing.

They watch us come along the path but don’t move, certain that they are the rightful owners of the place as it is they who keep it all year round. These large calm birds do not appear to be unduly disturbed by the seasonal comings and goings of their noisy neighbours.

We rest for a moment in the shade of a small carbet before carrying on with our visit.

The island drops vertically down to the sea and so by looking over the edge of the cliff we are able to observe the green turtles come to nibble the seaweed on the rocks below. We are on the dividing line between the oceanic waters and the coastal waters laden with silt. For a few days each year the water can be clear enough to be able to make out the shadow of an Atlantic goliath grouper living in the rocks around the island. The goliath grouper was one of the first fish species to be placed on the red list of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and although the species is classified as critically endangered worldwide, fishing for groupers is allowed in French waters even though it is forbidden by all our neighbours (Brazil, the Caribbean, Florida, and so on). That is why a study is currently being carried out in French Guiana, with the help of the reserve, to better ascertain the status of the local population.

We then leave the edge of the cliff, drawn by a background noise from behind a hedge of cadelamber cacti blocking our view. Incessant chirruping suggests a lot of activity. Sheltered by a raised hide we discover a platform covered by thousands of pairs of terns. There are both Cayenne terns and Royal terns in the colony.

Over 8,000 pairs of Cayenne terns come and lay their eggs each year on this half-hectare site, almost a third of the global population. When the island was turned into a reserve it had a spectacular effect on the species, whose numbers went from 300 pairs when it was set up in 1992 to over 8,000 pairs since 2005. As long as there is more than one beak’s length between the birds the two species cohabit well enough, but any bird landing in the wrong spot will be chased off from his neighbour’s nest with much pecking.

A larger tern with an orange beak catches my attention. It is a royal tern, of which 1,500 pairs come to the islands during the breeding season to rear their young. This species lays a single egg on the same platform as its smaller relatives and they raise their chicks at the same time. We are lucky enough to see half the Caribbean population of this tern gathered together in the same spot at the same time.

Carrying on around the island, we near the nests of the brown noddies. They sit directly on the rock on a little ledge on the cliff face, and the two adults assiduously protect their chick. One of the two adults flies off to dive on us, cawing, and we do not hang around so as not to disturb them any longer.

It is time to leave this observatory in the middle of the ocean and go back down to our boat and so head back to Dégrad-des-Cannes. As we advance there are fewer and fewer birds, one last Cayenne tern flies overhead as if to salute us, the port lies ahead of us, night is falling, and all is calm.

English

English Français

Français  Português

Português

![Photo de J-L Roustan, S. Hamel, S. Barrioz Frégate superbe [en bas] <i>(Fregata magnificens)</i>, c’est lors des parades nuptiales que le mâle arbore ce superbe ornement.](http://www.une-saison-en-guyane.com/uploads/galeries/usg6-le-grand-connetable/thumbs/thumbs_img_8327.jpg)

![Photo de J-L Roustan, S. Hamel, S. Barrioz Mouette atricille <i>(Leucophaeus atriclla)</i> la colonie de la réserve naturelle de l’île du Grand Connétable est celle qui se situe la plus au sud. Ces mouettes nichent du Canada à la Guyane. [Page de droite en haut]](http://www.une-saison-en-guyane.com/uploads/galeries/usg6-le-grand-connetable/thumbs/thumbs_mouette_atricille_roustan.jpg)

Télécharger l'article en PDF est réservé aux abonnés Web !

Télécharger l'article en PDF est réservé aux abonnés Web !

Pas de réaction

Pas de réaction Comment!

Comment!

Voyages avec Tooy. Histoire, mémoire, imaginaire des Amériques noires : Editions Vents d’ailleurs, 2010

Voyages avec Tooy. Histoire, mémoire, imaginaire des Amériques noires : Editions Vents d’ailleurs, 2010

Guyane. Produits du terroir et recettes traditionnelles. L’inventaire du patrimoine culinaire de la France : Editions Albin Michel, 1999

Guyane. Produits du terroir et recettes traditionnelles. L’inventaire du patrimoine culinaire de la France : Editions Albin Michel, 1999

Alunawalé, un voyage à travers les milieux naturels de Guyane : Office National des Forêts, 2009

Alunawalé, un voyage à travers les milieux naturels de Guyane : Office National des Forêts, 2009

Augusta Curiel, Fotografe in Suiriname 1904 – 1937 : Libri Misei Surinamensis, 2007

Augusta Curiel, Fotografe in Suiriname 1904 – 1937 : Libri Misei Surinamensis, 2007